Who is the villain?

Is the villain the leader who starts the movement? The demagogue who decides to rally the tiny cruelties that live within the hearts of people who think of themselves as good? Is it the person who blows on the embers of hatred until they finally catch and erupt into an all-consuming flame?

Or is it the person who finds themself in a position of power, and chooses not to put the fire out? Is the villain the person who chooses to sit before that fire, warming their hands?

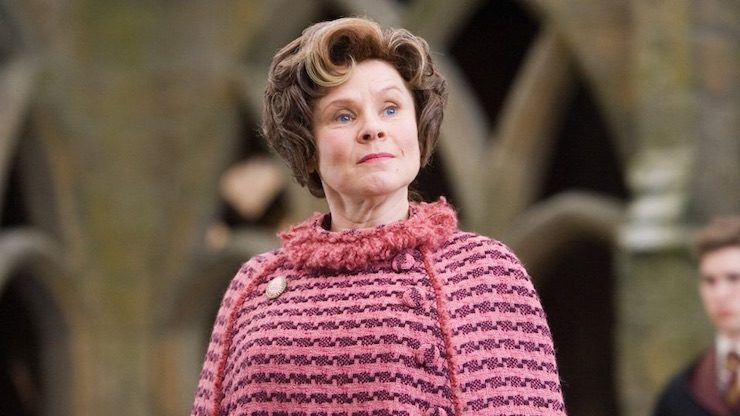

Dolores Umbridge has surely never thought of herself as evil. Evil people never do. They think of themselves as working for the betterment of the world they live in. Dolores Umbridge lives in a world that is populated by all sorts of people—werewolves and merpeople and muggles and wizards.

And she knows in her heart that it would be a better world if some of those people—the lesser people, the less important people—served people like her. Or died. Either one will do. Either way, they must be broken.

It would be a better world, she tells herself, for everyone.

And so she will work tirelessly—her shoulder to the wheel, her nights sleepless—until she has made her world the best world that it can possibly be.

We trust, often, that those in positions of power will use their power more for good than for evil. We trust in our systems: that those who do use power for evil will be removed, punished, pushed out by a common desire for good.

But then, we forget, don’t we? We forget that not everyone agrees on the definition of “good.” We might think of “good” as “everyone equal, everyone friends” while others think of “good” as “those people gone.”

We trust that the kinds of people who disagree with us—the kinds of people who would see those who are different from them dead, or destitute, or deserted—will be removed from positions of power. Because we think that surely they won’t be allowed.

But then we arrive at school one day and we look at the staff roster and there they are, smiling down at us, certain of their purpose.

And at first, we do not feel fear. At first, we rest assured that they will not be allowed to use their power to hurt people.

At first, we are comfortable.

Dolores Umbridge, sitting at her desk late at night, lit only by the light of a single lamp. Everyone else has gone home.

But she is sitting at her desk, drafting groundbreaking legislation. Language that has never been used before. Language that will change the lives of thousands of people. Language that will change the world.

Language that says that anyone who has succumbed to lycanthropy may not hold a full-time job.

Dolores Umbridge, pushing her law through until it passes.

Dolores Umbridge, changing the world.

When do we feel the first shiver of doubt?

Is it when the legislation is drafted that says that Those People won’t be allowed to hold jobs? Is it when the person who drafted that legislation smiles at us in the hall, because we aren’t one of Those People?

Is it when we see fear in the faces of Those People? Is it when we make the decision to look away from that fear, because we aren’t one of Those People?

Is it when we see the person who drafted that legislation take a child into a closed office for discipline? Is it when that child leaves the office with shame written across their face and blood dripping from their clenched fist?

When do we question whether or not the system will work to stop the person in power from doing evil things? When do we begin to doubt that it can?

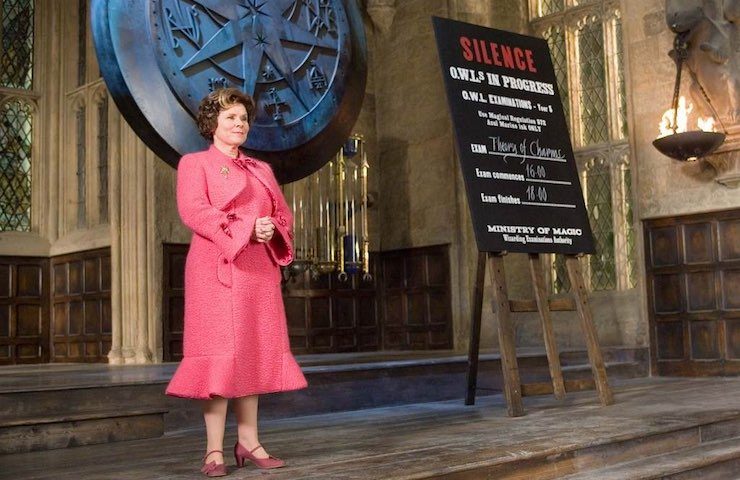

She attends a trial, and she has her first taste of real power. Real, true power. This isn’t the power commanded by a woman at her desk, by a woman attempting to trade favors to get a suggestion written into law. This is the power of a judge, watching a single person in chains tremble with terror. This is the power of command.

This is the power of fear.

This is a woman finding her calling.

Imagine looking out into a sea of young faces. Children, these—some as young as eleven, some as old as seventeen, but children. All certainly children.

Imagine looking at those faces and knowing that you have the power, in your interactions with those children, to make them feel fear or safety. Imagine knowing that you can teach them to guard themselves—or, you can leave them vulnerable. Imagine looking at those children and thinking, “Some of these, I will allow to die. Some, I will teach to kill.”

Imagine looking into those faces and thinking, “These, I must teach to hate.”

It’s not easy to lead.

Hogwarts has an immense impact on the culture of the wizarding world, no mistake can be made about that. And Dolores Umbridge is given an enormous opportunity—a tremendous one, really—to shape that impact.

And shape it she does.

Everything is going well at first. She’s working hard, banishing curricula that would harm the good and bright and pure future of her world. She’s teaching children discipline, and silence, and the importance of obedience in thought and word and deed. She’s promoted to High Inquisitor, and her grip feels so firm.

But then, damn. It slips, just a little, and that’s all it takes. The children organize, and they rebel. They have the nerve to call themselves an army. Child soldiers, that’s what they are, child soldiers in the war on order. She does what she can to shove them back into the molds she’s made for them, but they keep slipping out from under her, even when she gets Dumbledore out of the way and puts the full weight of her authority behind her efforts to make them obey.

And then, disaster. They succeed. They are victorious.

This, Umbridge learns, is what happens when you let your fist loosen for even a moment. This is the price of mercy.

We trust that the system will stand strong against evil. We hope that it will break before it allows us to bleed.

But sometimes, it doesn’t break. Sometimes, it doesn’t even crack.

Sometimes, it just… bends.

Dolores Umbridge finds herself overwhelmed by an embarrassment of riches. The Hogwarts thing didn’t go so well—she’s still shaking the dust from her shoes on that one. Trying to ignore the jokes about her humiliation, about how she was run out of the school, attacked by centaurs. About how she couldn’t shape their young minds enough to keep them from defeating her. Half-breeds and children.

She’s not going to let that get to her, though, because she’s back at the ministry doing her dream job. Doing important work.

Registering the Muggle-Borns.

Making a list, checking it twice. Making sure everyone who isn’t a pureblood wizard keeps their eyes on the ground. Writing informative pamphlets to make sure that everyone knows the truth—not the factual truth, not always that, but the deeper truth. The truth about how the world is, and about how it should be. The truth about the importance of Umbridge’s work. The truth about the Ministry’s purpose.

Order.

Purity. Above all else, blood-purity.

Dolores Umbridge, changing the world. And she knows she’s right about how to do it, not just because it’s in her heart but because it’s on the nameplate on her desk. She is in charge, asked to do this important work by the Ministry of Magic itself. And why would she be in power, if not because she sees the way that things ought to be, and isn’t afraid to take difficult steps to make it better?

Why wouldn’t she be in power, if not because she is right?

She shaped young minds. She didn’t count on how successful she would be at shaping them.

She taught them how to rebel.

That was her first mistake: every time her grip tightened, they learned a way to slip between her fingers. Every time she put up another wall, they learned to dig a deeper tunnel.

She taught them how to plan, how to organize, how to hide.

Buy the Book

River of Teeth

Most important of all: she taught them that evil can stand behind a podium, or can sit behind a large desk with paperwork on it. She taught them that evil can hold a scepter, or a wand, or a teacup. She taught them that evil can look innocuous. She taught them to question the people who look safe, who say that they are safe. Who say that they have your best interests at heart. Who say that they are inevitable, that they are a force for change, that they know best. She taught them that evil can wield institutional authority. She taught them that no evil is too powerful to be defeated.

Because of her, they learned to resist.

Evil is the demagogue at the rally, whipping his followers into a bloodthirsty frenzy.

Evil is the secret meetings, where the password is “purity” and questions are forbidden.

Evil is the ruthless figurehead, hungry for power, blood on her hands.

Evil is the people who look away, who trust, who obey.

Above all, evil is the thing that we fight.

Originally published in November 2016 as part of the Women of Harry Potter series of essays.

Hugo, Nebula, and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Their work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. They are a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to their work here. They tweet @gaileyfrey. Their debut novella, River of Teeth, and its sequel Taste of Marrow, are available from Tor.com.

Hugo, Nebula, and Campbell award finalist Sarah Gailey is an internationally-published writer of fiction and nonfiction. Their work has recently appeared in Mashable, the Boston Globe, and Fireside Fiction. They are a regular contributor for Tor.com and Barnes & Noble. You can find links to their work here. They tweet @gaileyfrey. Their debut novella, River of Teeth, and its sequel Taste of Marrow, are available from Tor.com.